Fractal Trees: Boundedness

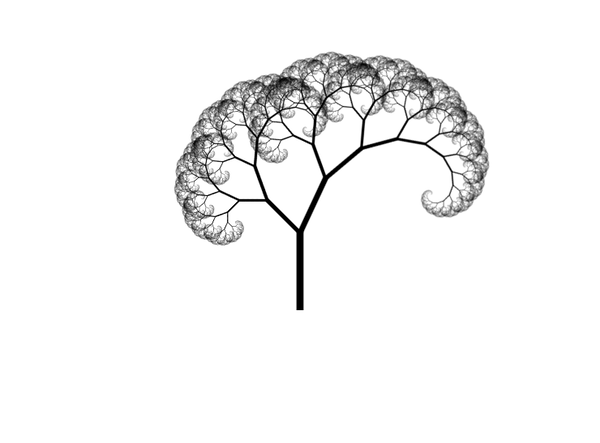

2020-09-06When does a fractal tree stay bounded, and when does it explode off to infinity? In the last post we looked at a few fractal trees and set up an interactive demo so we could get some intuition on what fractal trees and how their parameters influence how they look. Now let's dive into some of the math behind them.

If you play around with the demo you'll see that as you increase the scale parameters the tree quickly expands to fill the entire screen (though the demo automatically rescales things to counteract that somewhat). The demo only goes out to 100 layers from the root which is usually enough to be visually indistinguishable from an arbitrary number of iterations. However, in certain cases it may seem like the tree stops growing when really it has reached the limits of the demo. So the question is: when does the tree grow endlessly and when does it stay bounded? In order to answer this we'll need to set up some formal definitions so that we have a firm base to build from.

Definition 1:

A tree is a structure on the complex plane defined by four parameters: two rotation angles and two scaling factors . You could alternatively use two arbitrary complex numbers, but keeping the rotation and scale separate is useful later. A tree is composed of branches, a branch is a line segment on the complex plane and will be written as . The branches that make up a given tree are defined as follows:

- is a branch in the tree

- If is a branch in the tree, then and are also branches in the tree

In other words, at the end of each branch we can add two more branches by rotating and scaling the previous branch according to the tree's parameters. We could instead choose as the initial branch which might feel a bit more natural, but I like because it rotates the tree upright on a standard plot of the complex plane. This definition works well to showcase the recursive structure baked into these trees and is nicely compact and concise. However, it can be a bit difficult to work with when we want to start proving things. To that end, we'll also set up an alternative definition based on infinite series which will let us take advantage of a lot of powerful pre-existing math.

Definition 2:

A path is a sequence over the set . It indicates a sequence of turns taken starting at the root of a tree, moving higher in the tree with each step.

Given a path , let

be the sequence of offsets between branching points on the path, and

be the sequence of branching points on the path.

Lemma 1:

For any path and its corresponding sequence , is a branch in the tree for all

Show proof

Proceed by induction.

We have that and . Since is a branch in the tree, then is also a branch in the tree by the second rule in the definition of a tree.

Now, assume that is a branch in the tree. We have that

Therefore

And is a branch in the tree.

Therefore, by induction is a branch in the tree for all .

Lemma 2:

For every branch in the tree except , there is at least one path and corresponding sequence such that and for some .

Show proof

This is a fairly simple induction proof, but relies on structural induction rather than regular induction.

For the base case, we start with the children of the root: and . Each of these can be reached with any path that starts with or respectively. In that case you have for , and .

Now we assume that is a branch in the tree which can be reached by the path such that and for some . Another branch can be constructed using the rule involving and (the proof is identical for and ). This new branch is then:

If we take any path such that for and . Then we have:

Therefore if a branch can be reached with a path then both of its children can also be reached by a path.

And so by structural induction, we have that all branches in the tree can be reached by at least one path.

Theorem 1:

A branch can be reached by a path as defined above if and only if it is part of the tree.

Proof: Previous two lemmas

So what does all this mean? Essentially, we pick some path up the tree and specify it by the series of left and right turns you make each time a branch splits into two more branches. is then the branch you visit at each step in the path with one end translated down to the origin, and is the sequence of junction points you reach as you follow the path. Finally, you can reconstruct the path by connecting consecutive elements of the sequence. Most importantly, this view of picking a path up the tree is equivalent to the recursive definition.

Now that we have this all set up, we can put some bounds on our trees.

Definition 3:

A tree is bounded if all branches in the tree are within some radius of the origin. That is, for all branches in the tree for some

Lemma 3:

A tree with or is unbounded.

Show proof

We can prove this by contradiction. Suppose without loss of generality that and that the tree is bounded with radius . Take the path for all , and corresponding sequence . Let then

That is, we can find a individual branch in the tree whose length is greater than . Now, since we assumed the tree is bounded and is a branch in the tree,

Which is a contradiction. Therefore, the tree cannot be bounded with or .

Lemma 4:

A tree with and is bounded

Show proof

Let . Note , and for

Therefore .

Therefore, for any branch we have

And the tree is bounded.

The remaining case is when either scale factor is exactly one. Within that case are a few interesting subcases. For one, if we have and we get a tree with straight vertical line and the tree is unbounded. With , , and , the branches that don't shrink stay contained in circular loops and so you end up with lots of loops branching off of each other but the tree stays bounded. If and , then the tree is again unbounded. If and we end up with a single circular loop which is bounded.

Lemma 5:

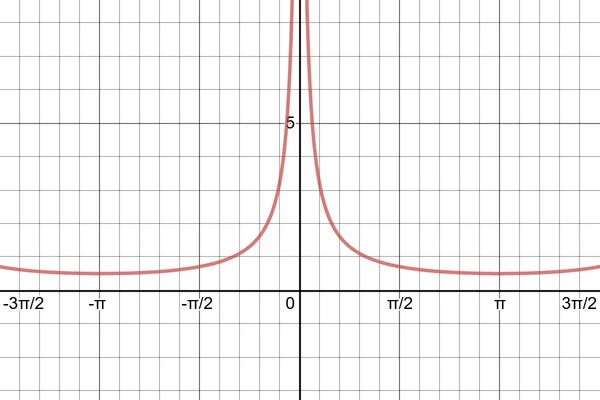

A tree with a scale factor and rotation angle forms loops of radius

Show proof

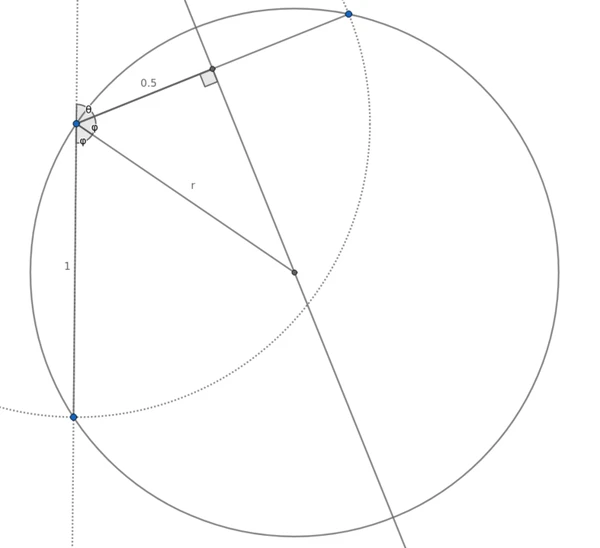

This can be shown geometrically.

You can also play with this interactive version on GeoGebra.

Here we have two adjacent branches with the second scaled by 1 and rotated by . The dashed circle indicates that the two branches have equal length. We can draw the solid circle with the three endpoints of the two segments on the border because any three points describe a circle{:target="_blank"}.

In order to derive the formula we need to first show that the two angles labeled are in fact equal. That can be done by connecting all three endpoints of the segments to the center of the solid circle and showing that the two triangles formed are congruent isosceles triangles which implies that the two angles are in fact equal.

Second, we use the fact that the perpendicular bisector of a chord passes through the center of the circle{:target="_blank"} to draw the right triangle shown in the diagram which connects the shared endpoint of the two segments, the center of the solid circle, and the midpoint of the second segment.

We can then use some basic trigonometry to derive the relationship:

We can then use and rearrange the equation to get:

You can show that all the branches that come from these parameters lie on the same circle by rotating the entire diagram by and repeating the same argument.

Note that as approaches zero the formula gives us a radius that approaches infinity. A circle with a radius of infinity can be thought of as equivalent to a straight line which is what we get with .

Lemma 6:

A tree with and is bounded.

Show proof

Take any branch and its corresponding path .

The path can be broken into a stretches of ones and twos. That is, a pattern like potentially with zero ones in the first stretch.

Every stretch of repeated ones is bounded since all such branches lie on a circle of radius . Therefore, any sum

Similarly, every stretch of repeated twos is bounded due to the lemma above showing trees with scale factor < 1 are bounded.

Let be sequence of run lengths for each stretch of ones and be the sequence of run lengths for each stretch of twos. Then we can break apart the repeated pattern of a stretch of ones followed by a stretch of twos to put a bound on the whole series. Note that each subsequent sequence of twos adds some number of factors, but we can put an upper bound on this by reducing to just one per sequence of twos since . That lets us bound the sequence as follows:

Which is constant with respect to , therefore every branch in this tree is bounded.

Lemma 7:

A tree and is unbounded.

Show proof

The goal here is to construct a finite-length pattern which ends with a branch facing straight up (i.e. with an angle of 0) which doesn't double back to the root of the tree. Repeating such a pattern of branches leads to a path which continues out in a way that avoids falling into a closed circle. To do this we'll use a pattern from group theory called the commutator, i.e. .

In particular we're going to make use of the fact that the total rotation over a sequence of branches is independent of their order (i.e. commutative), while the final position is not. We'll show that we can construct (or an approximation) as an integer multiple of which will be the inverse in this case. Then we'll show that the commutator pattern is a way to sequence these turns which satisfies the conditions above.

First, let's investigate which angles we can construct with a given branching angle. Let be a branching angle, it's obvious that one application of this angle from the root gives us a rotation of . A second application gives us an angle of . Note that this isn't the angle from the origin to the end of the branch, it's the orientation of the branch itself. So obviously we can construct the angle for any , but eventually that wraps around past so what unique angles does that actually give us? Well, we've constructed the Circle Group so we can take some results from there. At this point there is a divide between angles which are a rational multiple of and angles which are an irrational multiple of . We'll call an angle which is a rational multiple of a "rational angle" and an angle which is an irrational multiple of an "irrational angle."

Multiples of rational angles will go to finitely many unique angles. In fact, if the angle is with in reduced form, there will be unique angles at for . Notably, this set of unique angles is a subgroup of the circle group which means that for every angle that you can construct, you can also construct its negation (this is part of the definition of a group).

Multiples of irrational angles will go to infinitely many unique angles, and in fact any angle can be approximated arbitrarily well by an integer multiple of an irrational angle.

So, for a rational angle we can take as and as . We know that can be constructed by repeated rotations by by the argument above. For an irrational angle, we can take and an arbitrarily close approximation of which we can also construct by repeated applications of .

We then can take the sequence:

Where are selected so that and or at least approximately equal in the case of irrational angles. We can then reduce to as follows:

Which is undefined when , but in that case the tree is unbounded anyway because we have a straight vertical line. Similar holds for . Now the sequence above becomes:

This is non-zero whenever . Note that the last term in this series, before all the simplification, is . Therefore, by repeating this sequence of branches we can travel arbitrarily far from the origin and the tree is unbounded.

This proof does gloss over the irrational angle case somewhat. To be more thorough you would need to show that a close approximation of leads to a close approximation of the final term. However, the core argument doesn't change so this case is mostly omitted for the sake of brevity in an already long proof.

Theorem 2:

A tree is bounded if and only if one of the following is true (for some ordering of ):

Proof: Previous lemmas